Released 13 September 2024, Arman The Parman. Also hosted on GitHub

What is BitVotr?

PROBLEM: How can votes in an election be counted in a provably honest way (provable by anyone) without revealing the votes of individuals publicly, or to the government?

SOLUTION: BitVotr is a P2P computer protocol that can be used by democracies to run elections that result in a provably honest count. Voters can vote from the privacy and comfort of their homes with their computer, and can verify the total count is correct and their own vote has been counted.

Aims

Achieving the following three aims simultaneously is the innovation of BitVotr:

- Election count provably not manipulated (anyone can verify the total count is correct)

- Each voter can verify their vote was counted

- Voter privacy from citizens, election coordinator, and government.

An incidental benefit of BitVotr is the massive cost savings of running an election.

Overview

Each voter has a unique identifier which is a public key (for vote publishing), and also doubles as an onion address for P2P communication, and voting network organisation.

Voters use an open-source BitVotr App to connect online to the network, and verify the growing tally of votes – they can verify their own vote is included in the tally, that every other vote is valid, and that there are no double votes.

To accommodate those without technology access, a parallel regular vote – in person or by mail in, should be made available.

Eligibility

In current democratic systems, all voters need to prove some sort of eligibility to vote.

Although I have designed a way to bypass the need for an election coordinator, BitVotr’s initial aim is not to change the rules that any democracy has set up – eg voting age, citizenship, maximum single vote, equal power of votes etc. Eliminating the need for a central authority to organise voter eligibility is not the purpose of BitVotr, and is not something that has been solved to date. In any case, this is not a critical problem with the election process – the problem is how to run an election openly so any suspicious activity is publicly apparent, and can illegitimise the claim of victory.

Actually eliminating the need for a coordinator that oversees who is eligible to vote (eg there’d be a need to exclude foreigners and perhaps have age limits), would open the door to very different kinds of elections – perhaps those that can be called by anyone, not just by the system of democracy in the country; a true peoples’ election. There is a way to achieve this, but it would need to be a modification to BitVotr, not an alternative. It is discussed in the appendix.

BitVotr uses the democracy’s status quo methods to ensure no one is given more than one “ticket to vote”, but introduces public/private key cryptography to prevent anyone impersonating a voter, changing anyone’s vote, destroying votes, or tampering with the tally.

In order for a voter to be approved/identified, there needs to be some interaction with the voting coordinator. There is room for variation on how that is implemented, but the essential components of the BitVotr protocol are:

- The voter has a public/private key and only they know the private key (otherwise others, even the coordinator, can cast a vote for them). The public key is also somewhat private – known to the government, but not the general public, similar to social security numbers.

- The keys are part of a new Proof of Tax concept. If citizens simply create one-time keys for the purposes of voting, then the election coordinator can defraud the system by creating keys on behalf of citizens, stealing their votes. To mitigate that risk, a system parallel to voting is required. Citizens are to control their own private key, and submit their public key to the government in order for it to be associated with their identity and tax payment obligations (or even government benefits) – eg it can be linked to the SSN or tax file number; any documented interaction involving their identity, to later be able to prove ownership and acceptance of a public key.

- Tax returns should be signed with the private key (and acknowledged with the public key by the government) – then, whichever public key is being used by the citizen to pay tax, is the one the government has to acknowledge as being the real public key during an election. Using keys in this way also eliminates the need for leaking privacy – eg no need for citizens to publish their SSN or public key to the general public, or to use a web-of-trust; the latter being a privacy problem because it leaks information about who one associates with.

- Trying to defraud an election by making up public keys will allow a citizen to dispute that their genuine key is not being used, and they have a tax history to defend their claims in court. The new made-up keys will also cancel the citizen’s ability to sign their tax returns!

- The coordinator is responsible for publishing one valid voting public key per voter on a Public Key List (defrauding the list with fake keys will be apparent election fraud, as the total size will not stack up to population numbers).

- Those who decline the BitVotr system (or are unable to use it) can vote the manual way as before (in person, or by mail – it’s up to the democracies to decide that for themselves), but will lose their ability to verify their vote was counted.

- Those who do not wish to use proof-of-tax may opt out but they also automatically opt out of BitVotr.

Equipment necessary

Windows, Mac, or Linux computer, or access to a trusted person’s computer. Combining resources (multiple accounts on one computer) is allowable/possible, up to 10 per modern-day computer (this could be changed after results from testing).

Minimum computing power equivalent – a Raspberry Pi 4

Minimum drive storage required 50 GB (initial estimate) – external USB hard drive possible. Smaller storage is acceptable if the voter does not wish to verify the total count themselves.

Broadband internet connection with access to the Tor network

Method:

The Voting event is made up of three stages.

- Stage 1 – Preparation

- Stage 2 – Entering the Vote

- Stage 3 – Four voting rounds (submitting votes)

- Stage 4 – Publication

Stage 1 – Preparation

An open-source app, the BitVotr app, is made available for download. Using the app, voters will upload their public/private keys which is stored securely and ideally backed up. Loss of keys is regrettable, but various strategies can be employed. What if keys are lost or stolen?

The Public Key List of every registered voter is to be published well before the election date, allowing anyone to check their ability to vote, and dispute if necessary. Once on the list, the ability to vote is assured. Mass fraud at this stage, with denial of voting, will be apparent.

The list allows anyone to check the maximum number of votes that can be cast (equivalent to the number of keys on the Public Key List), and compare that with the size of the voting population they believe is true.

It is up to the election coordinator that no one has a double-vote, as is done currently, but if defrauded to any significant extent, the number of public keys would then exceed the anticipated number of eligible voters.

The identity of any public key holders is only relatively private, but this potential privacy weakness will be dealt with during the voting process, as will be shown during the explanation of the voting rounds. (Also see: Why merge votes? and Why RAFT clusters?).

During stage 1, the terms and conditions of the election are published by the coordinator.

The start date shall be set to the Bitcoin network’s clock, ie a Block Height, for very important reasons that will become apparent later. Provided humanity is not on the brink of extinction, the Bitcoin clock is almost as reliable as the sun coming up.

Variables for the election, such as the duration of voting rounds will be written into the BitVotr App code, and made available for download. The software will also be signed allowing voters to verify that they have a true copy of the correct version. Instructions to do this should be clear and easy.

Stage 2 – Entering in the vote

Prior to the election, all voters should access their BitVotr App and run the pre-election program:

1) Select their vote, and sign the vote with the digital private key (all made easy by pressing a button in the app).

2) Acknowledge the Bitcoin block to start the election, to be ready and online at the time

3) Download the Publik Key List (large file)

4) A completion signal could be sent to the co-ordinator (might not be necessary)

5) BitVotr will create a Tor hidden service using the private key, which results in the onion address server endpoint.

Stage 3 – Overview

The purpose of stage three is to accumulate the individual votes and merge them together, in order to obfuscate which key voted for which candidate. This is similar in concept to Bitcoin mixing transactions.

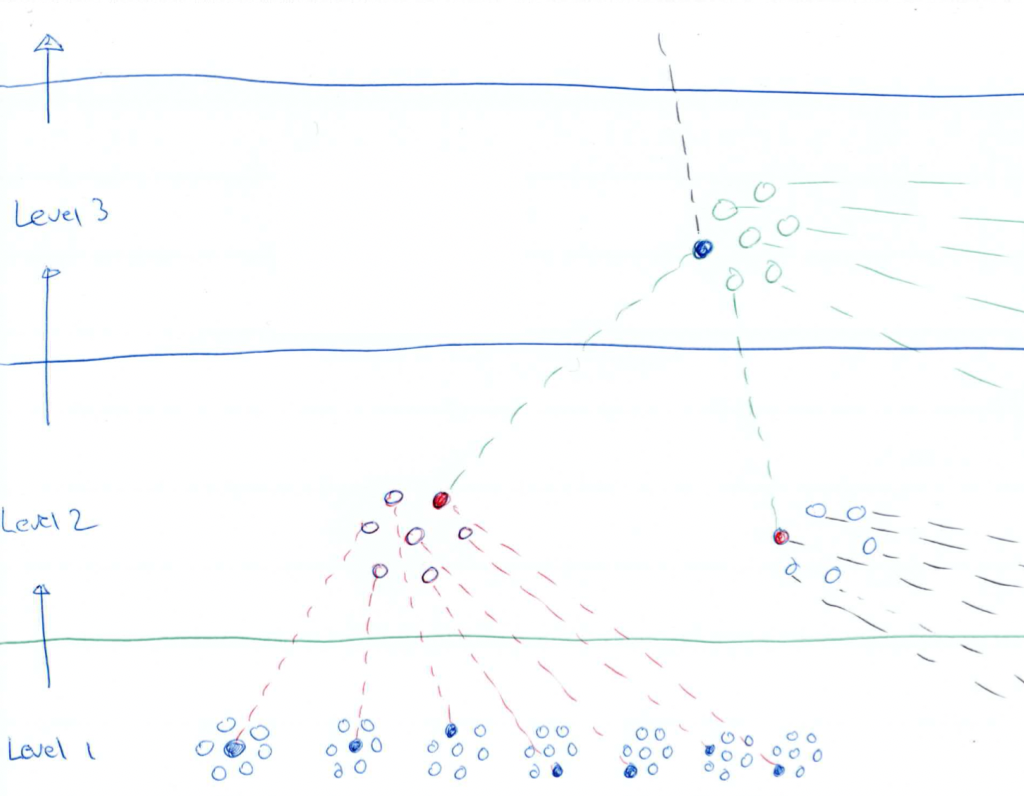

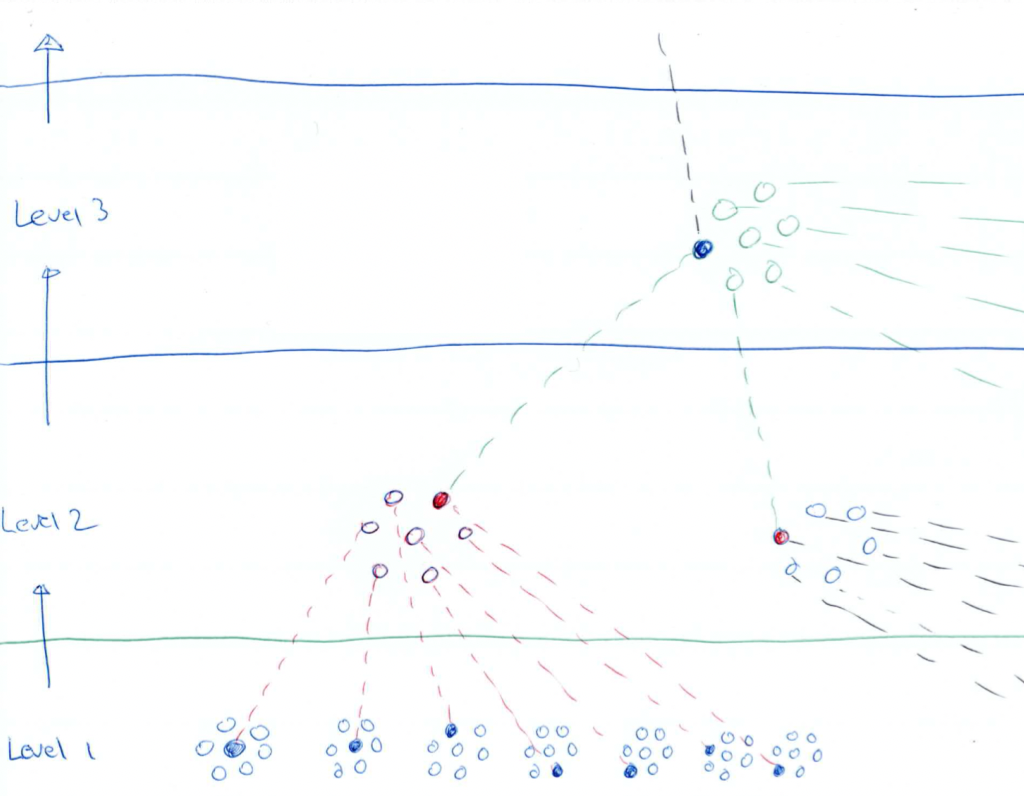

Vote merging begins with small groups, which subsequently merge with other similar groups until very large groups are formed, sufficient to hide individual voters’ preferences (necessary because the document ultimately becomes public). Which nodes merge with which others is deterministic based on the order of the public keys – not the original published order, but after they have been mixed by the Bitcoin clock.

As votes are being merged, individual nodes are verifying signatures to ensure the count is correct – similar to how Bitcoin nodes verify valid transactions.

The final merged document will contain the vote tally, and a list of public keys that voted, and attached corresponding signatures of the document.

Another purpose of this stage is to handle nodes that disconnect, which will be detailed.

Stage 3 – Voting Round 1

Time Period 1

Time periods are counted in Bitcoin blocks for easy agreement of time, and no need for central coordination.

The election begins at the pre-specified Bitcoin Block height, which marks the beginning of time period 1. This period lasts an arbitrary number of blocks based on network factors, yet to be determined.

The BitVotr App extracts the Bitcoin block and obtains its hash. The hash is then used to deterministically mix the order of the PubKey list (using prime finite fields).

Peer to Peer connections over Tor are made in RAFT-protocol clusters of seven (See why RAFT clusters?). The voters’ public keys are also their onion address for the Tor network.

Megaclusters of 16,807 nodes are formed (takes seconds), and maintain communication via levels of hierarchical RAFT protocol clusters explained later.

The system can handle people dropping out and reconnecting, and can handle low computing power. If the total pool of voters was 300 million, then there would be 17849.7 megaclusters. The incomplete cluster (0.7) can be managed by merging it deterministically and evenly with the others.

As long as a cluster has 4 nodes out of 7 alive, the ‘majority rule‘, holds, and the cluster can remain active and connected to lower and higher RAFT levels. When nodes that disconnect and don’t reappear in time, the remaining nodes flag their IDs, or the ID of their entire section if a section goes down, to a shared “dropped list” via a gossip protocol.

Time Period 2

At the beginning of this period, nodes will be linked to one of the megaclusters. It is possible that some nodes will not have participated at all, or are disconnected at this point in time for whatever reason. They will have until the end of time period 2 to join the megacluster. If they don’t reconnect in time, they still have the opportunity to vote in the ‘dropped round‘ or final round.

During this time period, votes are exchanged and verified within the RAFT cluster of 7 (level 1 of the megacluster), then the leader nodes of the clusters merge the votes into a NOSTR data structure which is then signed as a whole by each member in the cluster.

The merged signature is considered “approved” if it passes the Byzantine Fault Tolerance standard, which is more strict than the ‘majority rule’ which is applied to the connection status of the RAFT cluster.

The leader of the cluster then programatically signals to each member that they can delete the individual votes (for enhanced privacy). Once done, the cluster signals their work for Period 2 is complete.

Clusters that fail to reach completion status by the end of Period 2 (ie failed the Byzantine Fault Tolerance standard) are added to the ‘dropped list’ – that is, the entire cluster of 7 nodes no longer participates in the pyramid for the next time period.

Time Period 3

The leaders of each level 1 cluster (base of the megacluster pyramid) are members of the level 2 cluster “above” as well. One of the seven in level 2 becomes the leader and 6 others become followers (they still remain leaders of the level below of course, otherwise they drop down and get replaced). Note the leader of level 2 is also potentially a leader of levels above as well.

The level 2 leader co-ordinates the merging of each of the seven’s (with itself included) merged Nostr-Tally merged vote, and at the end of the round, they should all be holding a merged-vote of 49 votes, and at least 33 signatures from the lower levels. Thirty-three is the minimum required for Byzantine Fault Tolerance. If it is achieved, the group can progress to time Period 4. Otherwise, the entire group’s 49 voters are added to the dropped list.

Time Period 4

During this period, the group sizes are 343 in total (7^3, or 7x7x7 = 343) if none have been dropped.

In level 3, a leader is in a group with 7 other members. Each of them are leaders in their respective level 2. And each of those are leaders in level 1.

The level 3 members coordinate, together with their leader, a data structure with 343 votes in total. If 229 votes are collected by the end of Period 4, then the group has an approved merged Nostr-Tally and proceeds to the next Time period.

Time Period 5

The Nostr-Tally has up to 2401 members and needs 1601 signatures to be approved.

Time Period 6

The Nostr-Tally has up to 16807 members and needs 11205 signatures to be approved.

Stage 3 – Voting Round 2

The dropped list – Time period 1 to 6

The list can be extracted from any node as they are all in sync. They are all arranged in an apparently random but deterministic way like the first list. The pyramid structure will be the same as before, and the same stages will happen as before. Any that drop again or don’t show up are added to the final list – shared with all nodes.

One important difference in this round is that if a pyramid reaches the size of 2401, then failure to merge into the final 16807 does not drop the entire group into the final list. Instead, the 7 approved clusters of 2401 remain as is, and attempt a merge in Voting round 3. This design is so that the opportunity to vote doesn’t rapidly diminish due to connection problems, while still maintaining a reasonable amount of anonymity.

Stage 3 – Voting Round 3

The final list – Time period 1 to 6

Like the dropped list in voting round 2, the tolerance for failure during this round is also reduced. This time, ANY successful merge is accepted, and clusters that fail to merge simply stop trying and reach their final form.

Stage 3 – Voting Round 4

No merging is done in this phase. Any node that hasn’t cast a vote should do so, and stay online. Their vote will have no privacy from the voting coordinator. Users can decline this and send in a standard vote outside of the BitVotr system.

Stage 4 – Data Publication

Every node shall hash the tally it is holding and share the hash in a gossip protocol. All nodes generate a list of hashes representing the vote tallies, and add unique hashes to their list, ‘voting hash list’.

From this point on, the data is disseminated in 3 ways:

- Every node that wishes to verify has the voting hash list and can use it to connect to nodes and request data exchange.

- The voting tally, WITH its hash in an appropriate field can be published to NOSTR and shared between NOSTR relays. Anyone can search for the hash and receive the tally. The signatures are also published as separate NOSTR events – they are the signatures of the tally data. The event has the hash of the tally, the pubkey they are signing for, and the signature data. Extra NOSTR relays during the election would assist dissemination.

- Nodes can also share the merged tally and signatures over BitTorrent. BitVotr will prepare the files for sharing, prepare the torrent file, and share to a tracker. Those who are verifying the election can then search for the hash and the tracker will direct them to the download.

By getting all the tallies the vote can be quickly counted, and confirmation requires the downloading and verifying of all the signatures as well. It’s up to the verifier to decide how many signatures they want to collect to confirm the tally, in order to be satisfied the election was honest.

Appendix

Why the name, BitVotr?

The name is a mixture of Bitcoin, Voting, and Nostr, reflecting the design. While no data is required to be published to the Bitcoin timechain, it is used as the election clock, and also to extract future sufficiently-random data (block hash) that all voters can unanimously agree on. Nostr is used in the publication phase of the election to widely disseminate signed votes for anyone to download and verify.

The BitVotr App

This name is used generically. The app can be created by anyone and implements the rules of the protocol explained here. Any modification can be made, but the assurances of the protcol should not longer be expected.

How BitVotr borrows from Bitcoin and Tor private/public keys

Exactly how private key entropy is generated and stored is not part of the protocol, but a suggestion is to use BIP39 to generate entropy and then use that to implement cryptography based on the Ed25519 curve (see below).

In Bitcoin, a BIP39 seed phrase is a protcolised way to encode a large random number into words, typically 12 or 24. The words are converted to ASCII bytes (these are integers), and then it goes through a series of steps including a hash to generate a 512-bit private key.

At this point in the chain of events, public/private key cryptography is possible. Before this, the system is just a protocol to get to the private key, and done for ease of human recording with minimal chance of error.

Private keys are kept private and they produce public keys.

Private keys sign digital data/messages, and produce digital signatures (large numbers). People with private keys can demonstrate to others, the verifiers, that “the private key of the public key I gave you, has produced this signature” – and the others can verify easily that it’s true.

In Bitcoin it gets really interesting partly because the public key is inside the message being signed.

In BitVotr, the system of signing with private keys is used but the keys are slightly different. They are borrowed from the Tor network, not Bitcoin. Tor uses onion addresses, which are in fact public keys. While the keys are used for verification and encryption, they are also communication endpoints; ie secret IP addresses. When used in BitVotr, direct P2P communication with the public key owner is possible, and exchanging signatures directly beccomes possible.

To generate onion addresses, private keys are normally generated by the Tor program. BitVotr will bypass this and create its own onion private keys, using a custom protocol incorporating BIP39. BIP39, with words, creates a 64-byte integer as the seed, before making keys. BitVotr will do the same but in the last step will generate a 32-byte integer (using HMAC-256 instead of HMAC-512), and from that integer, will generate the private key. The cryptography for v3 onion addresses is based on Ed25519, which uses the twisted Edwards curve defined over the finite field with the prime:

known as Curve25519. As opposed to secp256k1 used in Bitcoin with the finite field over prime:

What if keys are stolen?

Stolen or lost keys would mean the key needs to be cancelled and a new one registered. This will unfortunately nullify the proof-of-tax history that can back a citizen up if their key was not properly accepted. It is up to each democracy if they wish to implement a rule such as – “a minimum of one signed tax history is required before a key is able to be used in an election”. There is no need for that to be mandatory in this protocol.

Is the vote immutable?

The vote cannot be changed because everyone’s vote is merged in large groups, thousands of signatures are valid for the large merged votes, and any tampering becomes evident by invalidating signatures. Immutability is not important per se, as long-term preservation of data is not the objective – rather what is important is the ability to know if the vote has been changed. There is no need to publish anything to the Bitcoin network, as nothing would be gained. Any manipulation becomes evidently invalid. Only the valid version of the count can persist.

Election time periods

The election begins at the specified Bitcoin Block height set by the election coordinator, “time period 1”.

Time periods last a somewhat arbitrary number of blocks based, and can be adjusted based on network latency factors, and results of pilot tests.

Using the Bitcoin clock, the hash can be extracted and incorporated into mixing the public key list in a deterministic way, without any possibility of knowing the value in advance, which would otherwise allow surveillance to know which voters will initially connect to which others – the weakest link in privacy. See here for how it is overcome.

Deterministic key index shuffle to randomise connections

The Pubkey List shall be organised in ascending numerical order, and indexed from 0 to max by the coordinator, and all BitVotr apps can verify it. Additionally, the data structure can be hashed to verify accuracy before proceeding.

Prime Finite Field Math

Using prime finite field math, the public keys’ indexes can effectively be randomised in a deterministic way as follows…

The largest index number that is also a prime number is found (using code and achieved in seconds). We shall call this number, “P”. This key and the ones above are set aside, leaving a P number of keys in the set (zero to P-1).

A special property of such a collection with a prime number of elements is that if you take ANY number and repeatedly add it to ANY initial index number, and use %prime (modulo prime) arithmetic, then every other number will eventually be hit exactly once before the value returns to the original. For example…

Numbers 0,1,2,3,4,5,6 are in a set with 7 elements, and 7 is a prime number. We can take ANY number, let’s say 10. With modulo 7 arithmetic, 10%7 is the same as 3. Now let’s repeatedly add 3 to any of the 7 elements, let’s arbitrarily start with 4.

4+3%7=0

0+3%7=3

3+3%7=6

6+3%7=2

2+3%7=5

5+3%7=1

1+3%7=4

Note that we used modulo twice to go from 10 to 3 and then used it again in the equation – that doesn’t matter. We could easily have added 10 to each number and used modulo later. As long as it is done just before getting to the answer, it doesn’t matter. You can even apply it to every number and it won’t make a difference.

In the above example, we started with 4, got to 0, 3, 6, 2, 5, 1, and then back to 4. Every other number was “hit” on the way back to 4.

With numbers in the millions, in a prime set, adding a hash (potentially up to 2^256) to each number will produce a new set with no overlap. Notice in the example above, the same number was added to each element and the resulting numbers only occur once (0,3,6,2,5,1,4). Shuffled in ascending order, 0,1,2,3,4,5,6

With a large enough set and a large enough number added, the 0,3,6,2,5,1,4 type of result, with millions of values, will seem random and unpredictable in advance. Not being able to predict how the shuffle will occur is a result of using a FUTURE Bitcoin hash value.

Mixed_index_of key = key_index + starting_Bitcoin_block_hash % prime_of_set

No one can know the future Bitcoin Block hash, so no one can know the future calculation that will be done in advance. Also, even though the Bitcoin hashes have about 19 leading zeros, the numbers are still incredibly large and sufficiently large for the purpose of mixing the set.

Why merge the votes?

The weakest link in privacy is that the public key is known to the Voting Coordinator (VC). We can’t allow a situation where data centres can be infiltrated to track who voted for who. To solve the problem, individuals can randomly (and deterministically) share their vote with another person (anonymously, as they are known only as public keys) and their votes are merged and the tally verified between them. Then they merge their vote with other merged groups and the tally of votes gets bigger. As the merging continues the anonymity of the vote for each public key increases. All of this is directed at protecting privacy from the VC (individuals cannot determine who is behind any given public key unless it is voluntarily revealed).

To determine the vote of a particular individual, the VC would have to interrogate other members during the initial merging stages (who pairs with who can be determined only after the election begins), and demand to retrieve deleted data from the computer. While theoretically possible, doing this at scale is practically impossible and an acceptable weakest link of the BitVotr system.

Why RAFT Clusters?

First, we must answer, “why have clusters?” Then, “why RAFT?”

If merging one to one, then too much dependence is placed on another individual being online for a vote to get merged and continue to merge with others. Having a group of seven is a balance between not relying on only one person, increasing initial merge privacy, and computing power (large clusters demand more power, and 7 is estimated to be reasonable for a Raspberry Pi 4).

An individual can drop out and the remaining people in the group can continue on. But with 1 to 1 merges, any connection dropout automatically will cancel the voting ability of the connection partner. Clusters introduce resilience to such dropouts.

Using the RAFT protocol, reliable agreement in the state of a changing document (the merged vote in the cluster) can be achieved.

RAFT protocol clusters

Information about what the RAFT consensus protocol is and how it works can be learned directly from one of the creators in an excellent lecture he released on YouTube.

To summarise, clusters of computers communicate initially on equal footing in a P2P network, and I’ll call each a “node”. Then following the protocol, a leader is chosen for the cluster (achieved by randomly-timed self-nomination, then verification by followers, vote, and approval). The leader communicates with the other “nodes” which become followers. The leader directs entries to be made in each of the follower’s logs (and its own) using a system of communication that allows for an agreed version of the log to exist.

The purpose of the RAFT design is to achieve consensus between nodes in a shared document state, while tolerating disconnections from the group, including the leader, splits in network communication, and having incorrect versions discarded – it is said to be “crash fault-tolerant”.

Malicious actors need to be considered also, but BitVotr uses a different system overlaid on top of the RAFT protocol to do that. This involves using Byzantine Fault Tolerance for VOTE/SIGNATURE approval, not for the health of the p2p network. This is discussed elsewhere.

RAFT Megaclusters

With millions of voters, their computers (all with variable computing power) will not be able to tolerate RAFT consensus communication. To overcome this problem, a Hierarchical RAFT system will be used. Clusters of 7 will elect a leader to join a higher-order cluster. Every initial cluster shall eventually be part of a pyramid of 7x7x7x7x7 voters for a total of 16,807 voters in each pyramid. Their vote and signature data should be uniformly agreed on, and become final – each member in the pyramid ends up with an identical copy.

Why are clusters in groups of 7?

Keeping cluster size small reduces the burden on weaker computers. But increasing the number increases the tolerance to faults. with a group of 4, 5 or 6, only 1 fault can be tolerated, and 2 would cause a failure according to Byzantine Fault Tolerance rules. Having 7, 8, or 9 can tolerate 2 faults but not three. Without any known evidence, 7 was thought to be a good balance, but this can be changed depending on how such a system performs in the real world and pilots.

What if a RAFT group fails ‘majority rule’ and cannot maintain a connection to the levels above?

If this happens, there may be time for the group to regain connection. It depends if that segment contributed to the merged tally that all the other leaders have approved. At that point, a disconnection would mean signatures from that segment can not reach the higher level, impacting the number of signatures collected, and risking a Byzantine Fault.

But if the disconnection from the group happens before the merged tally, then after some timeout, the group will create a tally excluding that disconnected segment, and work towards achieving sufficient signatures on a smaller tally. If the lost segment reconnects, the group shall continue to finish its work on the smaller tally, and only after it has completed the task, it would start over and and work on the larger merge. If they finish in time before the period is over, the larger merge shall count and the smaller one is discarded. If they don’t finish the larger merge in time, the original connected nodes will push on with the smaller merge, and the disconnected segment will be added to the drop list. In this way, the original nodes are not disadvantaged by a disconnection and slow reconnection.

What if there is network isolation in a RAFT cluster, resulting in a split group with two nodes (one from each split) that think they are leaders of the whole group?

The RAFT protocol takes care of this so that neither of the isolated leaders can progress to the higher level until they get a majority of the vote. This prevents two leaders from presenting themselves to the higher levels and causing confusion.

How do the nodes in the higher levels know who else is in their cluster?

For level 1, all the nodes can simply look up the mixed index to see who is adjacent to them (This is the entire public key list AFTER it has been deterministically mixed over a finite field). They can calculate who should be on their list. But the higher levels need to know who are leaders from the lower levels. They do this by asking the group who their leader is and if that leader has a majority. If so, that node is elevated to the higher level and partakes in electing a leader at that level.

Majority Rule

The majority rule is used to ensure a reliable merged vote in a RAFT cluster. As long as the majority of nodes agree, with absolute certainty, the merged vote state will not be faulty, and it can tolerate splits in communication – this is a feature of the RAFT protocol.

Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT)

This tolerance level assesses the system’s resilience to malicious actors, not just general faults, who may attempt to manipulate the result. It is distinct from the factors that determine the overall health of a Raft cluster.

For a merged vote to proceed and merge with others, both the RAFT cluster must be healthy, and BFT conditions must be satisfied.

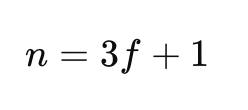

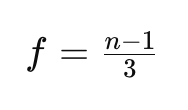

The minimum according to this standard depends on the size of the group. For a group of seven, the minimum is 5. The calculation is:

Where n being 7, f can be calculated as 2, the number of tolerable faults.

What if a group fails Byzantine Fault Tolerance and exits the merging cascade, does it reduce the chance of the remaining groups to achieve approved merges?

Not really, because the missing group does not count towards the fault tolerance level. Eg, in a level 3 group that would normally have 343 signatories, if one of the level 2 groups were missing from the previous round, then only 294 votes are being merged. The tolerance level then changes to 197 instead of the original 229. This change is based on the BFT formula.

The Dropped List

The dropped list is known to all nodes and is not to be deleted. Similar to how Bitcoin Nodes maintain a mempool of transactions and propagate the contents to other nodes via a gossip protocol, the dropped list is maintained by all nodes and should be identical.

It is used to give those with connection issues an opportunity to participate in subsequent rounds, and calculate the connection patterns in a random but deterministic way. Deterministic is essential, to allow all nodes to independently come to the same conclusion about which node connects to which, and in no way can it be predicted in avdance (protects privacy by making it difficult to prepare to snoop).

The Dropped Round

If nodes decline or are unable to join for the dropped round, then their vote may be cast in the ‘final round’. If that opportunity is missed, they’ll have to submit their vote outside the BitVotr system. One such way is to cast a NOSTR event and sign their vote with a time stamp. It is up to the Voting Coordinator if this type of vote is to be allowed – voters can still use the BitVotr App to cast a NOSTR vote. If a vote in the BitVotr tally is found, then no other vote from that public key is considered valid.

Explaining Onion Keys

Onion addresses are a form of public keys and are derived from private keys. The cryptography is based on the elliptic curve, “Curve25519”. Onion addresses are used like IP addresses, but they can also be used in all the other ways public/private key cryptography can, including signing and verifying messages.

On Privacy

Level 1 is the weakest link in privacy – each node knows the other’s vote with certainty, but does not know who they are. With subsequent merges, the list of voters and the tally grows, and so does the obscurity of which key voted for who. Eventually, all groups will be merged and tallied. As the nodes merge their data, previous data is dropped and deleted to protect privacy; this removes the risk of subsequent interrogation of individuals for initial connection data.

Examples of merging votes

The life of a signature is as follows:

Initially, a voter finds themselves in a cluster of 7 others. They share their vote with the leader (cluster partners are predetermined from the mixed pubkey list).

The leader merges the 7 signatures, signs, and shares all the documents with all the followers.

Each member sees the votes of the others and can verify the tally.

The tally accumulates 7 signatures.

The leader of the cluster is connected to 6 other leaders that form a level 2 cluster. One of them is the leader of that level 2 cluster.

In the same way as the level 1 merge, each of the level 2 followers shares their merged signature list with the level 2 leader, and a larger merge is formed. The other level 2 nodes do not see the individual signature of the other 6 nodes, only the merged version. In this way, the privacy of individuals increases as the vote tally progresses up the levels.

Importantly, every document seen by level 2 members is shared with their level 1 followers, so there is no trust of the count to anyone.

When level 1 followers are satisfied, the level 1 leader can approve the larger merge in level 2.

This process continues up to the tip of the pyramid.

Verification during merges

When merging, these are the conditions that need to be met:

- Each node signs the merged data and shares its signature

- Signatures are added to the merged event. If all signatures are valid, then the total is hashed for identification, and shared to levels above.

Managing dropped connections

When a node within a cluster disconnects, if it is a leader, the absence will be noticed and a new leader gets elected following the RAFT protocol.

If it is a follower, the cluster continues on, as long as there is a majority of nodes remaining (4), then the process of merging can continue, but without the missing nodes.

Reconnections can be accepted, the merge being repeated with more votes included.

Should a merge be completed, and then a node disconnects, then they are unable to contribute to the signing of the merged document or any subsequent signatures of higher-level merges. This counts towards Byzantine Fault Tolerance, and if the threshold is not met, the merged document fails and all members get added to the dropped list for a repeated attempt later.

The failed merge does not necessarily condemn the entire pyramid, but just the section that fails the tolerance threshold.

What if there are various size megacluster-pyramids at the end?

This won’t be a problem for the election validity; only some impact on privacy. The largest pyramids will be the most private and the smallest will have somewhat less privacy.

Managing rouge nodes

A rogue node might provide invalid signatures – it will be rejected. As long as there are sufficient honest nodes providing signatures, the merging of votes can continue without the rogue node’s vote.

Repeated connections and disconnections are managed by making sure the remaining nodes complete their merge before attempting a larger merge that includes the rogue node.

Tor network and load

With a large election, it could be that the Tor network becomes overwhelmed.

Individuals can be encouraged to temporarily run a Tor middle relay to contribute to Tor bandwidths.

Depending on pilot tests, time periods can be titrated (lengthened or shortened) for expected Tor network performance.

How can it work in practice?

BitVotr is not something easy to implement logistically, particularly with a population not ready for such technology. It will require a transition period and testing, but in the future, using such technology will be second nature for most of the population.

BitVotr will require the willing participation of the government and the existing Electoral Commission. It might need to be widely demanded for this to be implemented, or a highly successful pilot might be needed.

Can’t people sell their votes? Isn’t that a problem?

If selling a vote is illegal (even though politicians buying votes seems to be acceptable), then it is not the design of BitVotr to make that impossible. Many illegal things are possible and not the obligation of inventors to prevent them from being possible.

Having said that, if that is such a concern for a country that BitVotr wouldn’t be adopted, then in-person voting can still take place in conjunction with BitVotr. This would be far more cumbersome and expensive, but at least citizens will still get the opportunity to independently count and verify the election result.

What if someone abandons their right to vote digitally, can’t a rogue government employee steal their vote?

This fraud cannot go unnoticed because the people relinquishing their right to vote digitally will turn up in person to vote by paper. They will then be turned away because they’ve already been registered to vote digitally.

Because the keys used don’t have a tax history (or signature interaction with government services) then those votes can easily be disputed.

Eliminating the central coordinator (Future potential implementation)

This involves a mature system of decentralised encrypted digital IDs, and the use of zero-knowledge proofs. It allows an election to be organised in a decentralised way, being promoted by anyone who can gather the momentum. Despite keeping votes private, the system can ensure no more than 1 vote is possible per person, while maintaining privacy. It also avoids the need for a “web of trust” which initially sounds nice in theory, but hurts privacy as it links publicly the people you may know or associate with.

An encrypted digital ID (eDID) is a document anyone can generate and then encrypt with their private key and publish openly. No one can read it unless approved by the individual, and logical statements can be proved with the data inside without actually revealing the data.

For example, picture a name in plain text at the header of a document; below that, the encrypted section can contain any information the individual wants to be able to prove about themselves. For the purpose of BitVotr, they’d need an onion address (they should keep the private key to the onion address safe), a large random secret number (for generating more deterministic keys as needed) and one or more official government ID documents in digital format with text fields about the contents.

When they add say a Driver Licence, the issuer can confirm using a ZK proof that the user has updated the digital ID. The issuer can then sign a message that might read, “I approve digital ID with hash: —– contains a valid Driver Licence”. The voter can then store the newer version of the ID and the signature of the issuer and their public key in a log file/database associated with the ID. All of that can be encrypted and published to servers like NOSTR for retrieval when needed.

To remove the need for an electoral coordinator, the announcement/advertisement of any proposed election should come with several onion addresses for spawning the P2P network. It should also come with the block height times for the election conditions. At the specified block time, users can connect to the initial seed onion nodes and submit the encrypted digital ID with a zero-knowledge proof to prove their connecting-onion-address is included in the ID provided. Their name does not need to be divulged, only that their ID is valid and they have an onion address. In this way, a voter is proving their identity, and their onion address, making sure that they are eligible to vote, and cannot vote twice (as only one onion is possible in a digital ID).

At this point, a system is needed to organise nodes as they get approved and vetted by a threshold of random nodes.

Once all the nodes are vetted. A final list can be made from which voting rounds can begin.

The final list can be in a predefined order, say numerically ascending, so that all nodes will agree on the state and order. It does not need to be mixed as no identities are revealed, but if it is deemed necessary, it can be done deterministically by using finite prime fields as described earlier.

Help support me develop BitVotr

On-chain or Lightning